Objectives

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- explain the concept of program evaluation

- implement a step-by-step approach to conducting a program evaluation using a logic model

- be able to integrate program evaluation into the ongoing activities of your program

Introduction

Program evaluation focuses on questions of program processes (e.g., Are we implementing the program as originally designed?) and outcomes (e.g., Are we accomplishing what we set out to do?). In this chapter we provide tools and tips for conducting a robust program evaluation for your postgraduate training program. We discuss the importance of program evaluation and describe how to integrate it into the ongoing operation of your program.

What is program evaluation?

Program evaluation is formally defined as the systematic investigation of the quality of programs for the purposes of decision-making.1 Unlike research, which focuses on generating new knowledge in a field primarily for the use of other researchers, program evaluation focuses on utility or generating information that can be used by those directly involved in the program for the pragmatic purposes of adjusting a program’s goals and/or making decisions about whether or not a program should continue operating in a particular direction. Accordingly, program evaluation encompasses aspects of quality improvement, but it can also examine larger questions of program direction, efficiency, feasibility and viability. It is important to remember that a program evaluation can seek to evaluate an entire training program or focus on specific elements of the program that may be unique, new or in need of a revision.

Getting started with program evaluation: a five-step approach

Although program evaluation is a relatively new field,2 there are many different models and applications of program evaluation.3 Drawing from those models, we have identified five common steps that anyone can use to get started with a program evaluation initiative. If you would like a specific example in medical education or a more detailed description, please refer to Van Melle (2016)4 or Kaba, Van Melle, Horsley and Tavares (2019).5

1. Gather key stakeholders

A stakeholder is defined as “someone what has a vested interest in the evaluation findings.”6 Because program evaluation is concerned with utility or ensuring the evaluation findings are actually used by key decision-makers, it is important to have those responsible for program leadership, implementation and operation involved in your program evaluation right from the beginning. Early engagement is particularly important when engaging with stakeholders related to equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). They may not all need to be part of your core evaluation team or be present at every meeting, but you will want to consult with these individuals and get their input as data are reviewed and key decisions around program adaptation are made. So your first step is to identify key stakeholders in your program and to make sure they are included in the program evaluation process.

2. Create a logic model

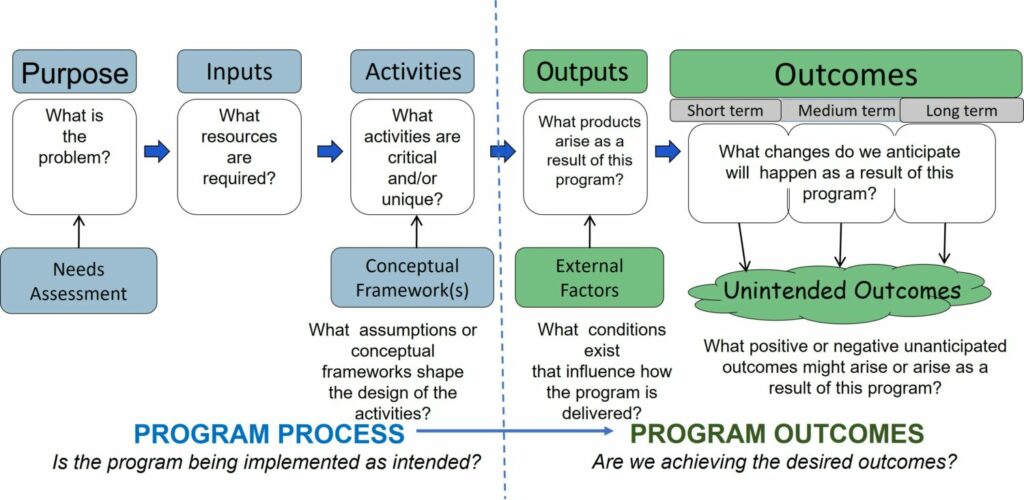

Now that you have your key stakeholders engaged, the next step is to identify the focus for your program evaluation. A program evaluation can address questions of program process or outcomes. That’s where a logic model comes in. A logic model is a tool commonly used in program evaluation to build an understanding of how a program is supposed to work, that is, the relationship between the program components or process and the program outcomes4 (see Figure 25.1).

Figure 25.1 – Program evaluation logic model. Adapted from Van Melle E. Using a logic model to assist in the planning, implementation and evaluation of educational programs. Acad Med. 2016;91:1464.

As shown in Figure 25.1, a needs assessment forms the starting point for creating a logic model and leads to a clear understanding of the purpose of the program. By conducting a needs assessment you will provide your stakeholders with evidence that it is well worth dedicating the required resources to your program. These required resources are shown as inputs on your logic model. Ultimately these inputs are organized into program activities. In creating a logic model it is important to identify those activities that are truly key or critical for the operation of your program. Finally, to complete the program process side of the logic model, you can identify the underlying concepts or theories that inform how your program activities are organized.

The right-hand side of the logic model describes program outputs and outcomes. Outputs are the products affiliated with the program (e.g., number of participants, number of times the program has been delivered). Outputs are simply descriptors of the level of program activity. These may be influenced by external factors such as the timing of program delivery. Outputs do not speak to the quality or effectiveness of these activities. That’s the role of outcomes. Outcomes describe the actual changes in behaviour or qualities that we expect will occur as a result of the program. For example, the Kirkpatrick model organizes outcomes of any training program into four levels: (1) reaction, (2) learning, (3) behaviour and (4) results.7 Each level builds on the last and so there is a temporal quality. You would expect to capture level 1 outcomes (reactions) during or immediately after program delivery, with level 4 outcomes (results) occurring downstream from program implementation. This temporal relationship is described generically as short-, medium- and long-term outcomes in the logic model. Finally, because programs are often complex, it is not always possible to anticipate all possible outcomes. This is represented by the “unintended outcomes” component of Figure 25.1.

Each program will be at a different stage of development. Some may be well established, while others are still under development. This will become apparent as you complete the first draft of your logic model. The intent of this step is not to create a perfect logic model but rather to complete as much of it as you can, leaving room for additional drafts as the evaluation progresses.

3. Prioritize your evaluation questions

As you complete your logic model it will become apparent that you can ask many different evaluation questions that go well beyond examining outcomes. Working from left to right on the logic model, you may wonder:

Are we really convinced that there is a need for this program? In this case you may want to focus on conducting a needs assessment as a priority for your program evaluation.

Do we have sufficient resources to implement this program? In this case you may want to focus on examining inputs.

Are we implementing our program as intended? In this case you may want to focus on examining how the program is actually operating. This is often referred to as the fidelity of implementation.8

These questions fall under the umbrella of a process evaluation. Moving into outcomes, you may want to know:

What is our program producing? In this case you may want to focus on examining the actual numbers or outputs associated with your program.

Are we achieving the specific changes we set out to accomplish? In this case you may want to gather data about the specific changes that can be attributed to the program.

Finally, it is important to remember that you cannot anticipate everything when creating a logic model. You may have a sense that some unintended outcomes are emerging that are important to capture.

Given the multiple possibilities, it is important to prioritize with your key stakeholders your most important evaluation question(s), remembering that a good evaluation question should:

- address an issue of key concern to your program stakeholders;

- be answerable (that is, not philosophical or moral);

- inform the progress of your program in a timely fashion;

- be feasible to examine; and

- be phrased in a neutral fashion (that is, it should not assume a positive or negative result).

Furthermore, consider the evaluation question(s) that may be important to develop from an EDI lens. What voices are not adequately represented in your stakeholder group or program? What are the challenges that exist for underrepresented or marginalized residents? Have you engaged with diverse residents as stakeholders in your development of the evaluation question(s)?

4. Gather your data

Just as with research, it is important that your method for data collection match the nature of your evaluation question. For example, if you are gathering perceptions or are centring underrepresented voices, qualitative approaches are probably best. If, on the other hand, you are interested in different types of behaviours adopted as a result of your program, you may wish to use a more quantitative approach. And of course, using mixed methods, where qualitative and quantitative methods are deliberately combined, is always an option. Regardless of the method you choose, balancing feasibility and credibility with practicality is a key aspect of program evaluation. Unlike research, where you may gather data over an extended period of time, program evaluation relies on timely data collection for the purposes of enhancing decision-making. The challenge is to make sure that the methods you use are well thought out and balanced in light of the need for timely data collection.

5. Act on and disseminate your findings

Data interpretation should be conducted jointly with all stakeholders at key points throughout the program evaluation. This approach maximizes the likelihood that that the findings will actually lead to program changes. The earlier and more often you can engage your stakeholders in making sense of and acting on the data, the better. Furthermore, the act of reflecting the data back to the stakeholders from whom the data were collected signals that you value their opinions or experiences; this can have a remarkable effect on the implementation process.9 Additionally, for EDI-focused questions that may contain sensitive data that is difficult to anonymize; it is prudent to ask the participant or stakeholders for advice on how to discuss this information in a psychologically safe manner.

There may be times that you would like to publish your findings as part of a peer-reviewed process and so may be reluctant to formally share your findings early on. Indeed, a program evaluation that has a clear conceptual framework or ”theory of change”10,11 and builds on the existing literature should be considered as educational scholarship and so suitable for publication.12 Creating a technical report in which you describe your progress in a timely fashion but do not include all details, such as specific methods or implications, allows you to share your findings as part of a program evaluation while leaving open the option of formally publishing your evaluation efforts down the road.

Building capacity for program evaluation

Given that programs are continuously evolving, program evaluation is best undertaken as an ongoing process.5,8 Accordingly, you can consider ways of building in program evaluation as an ongoing activity within the operation of your program.

Helpful hints

Your logic model will evolve over time

In creating a logic model, the task is simply to get the conversation started. So focus on creating a logic model that is “good enough” and label it as a draft. You will probably continue to discuss and revise your logic model and create new drafts as your program evaluation unfolds and as your program develops over time. Creating and sharing your draft logic model is a great way to get ongoing engagement and buy-in from all stakeholders.

Reach out for expertise

Program evaluation requires expertise that you may not have immediate access to within your program. At many academic health science centres, evaluation expertise can be accessed through different departments (e.g., education, public health, community health and epidemiology, EDI/Anti-Racism offices). You do not need to have people with such expertise in your core stakeholder group, but it is well worth your time to reach outside the group to access advice that can assist in your program evaluation.

Keep your program evaluation simple

There may well be a trade-off between conducting the perfect program evaluation, working with the available resources and creating timely data for decision-making. A good rule of thumb is to keep your evaluation simple, recognizing that this is an iterative process. Opportunities for improvement will always be available. The main goal is to generate a process and data to inform decision-making.

Conclusion

Program evaluation is a specific field distinct from research and quality improvement in that the main focus is always on providing timely data for decision-making and program adaptation. To ensure that results are used, engaging stakeholders is a key feature of a robust program evaluation. A program evaluation can encompass many different questions examining both program processes and outcomes. Accordingly, program evaluation can be undertaken at any time in the development of a program.

References

- Yarborough DB, Shulha LM, Hopson RK, Caruthurs FA. The program evaluation standards. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2011. p. xxv.

- Fitzpatrick JL, Sanders JR, Worthen BR. Program evaluation: alternative approaches and practical guidelines. 3rd ed. Boston (MA): Pearson Education; 2004.

- Stufflebeam DL, Coryn CLS. Evaluation theory, models & applications. San Franscico (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2014.

- Van Melle E. Using a logic model to assist in the planning, implementation and evaluation of educational programs. Acad Med. 2016;91:1464.

- Kaba A, Van Melle E, Horsley T, Tavares W. Evaluating simulation programs throughout the program development life cycle. Chap. 59. In G Chiniara, editor. Clincial simulation: education, operations and engineering. 2nd ed. San Diego (CA): Academic Press; 2019.

- Patton MQ. Essentials of utilization-focused evaluation. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2012. p. 66.

- Kirkpatrick DL, Kirkpatrick JD. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. 3rd ed. San Francisco (CA): Berrett-Koeler Publishers; 2006.

- Hall AK, Rich JV, Dagnone D, Weersink K, Caudle J, Sherbino J, et al. It’s a marathon, not a sprint: rapid evaluation of CBME program implementation. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):786–793.

- Funnell SC, Rogers PJ. Purposeful program theory: effective use of theories of change and logic models. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2011.

- Bordage G. Conceptual frameworks that illuminate and magnify. Med Educ. 2009;43:312–319.

- Van Melle E, Lockyer J, Curran V, Lieff S, St. Onge C, Goldszmidt M. Toward a common understanding: supporting and promoting education scholarship for medical school faculty. Med Educ. 2014;48:1190–1200.