Objectives

At the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- create a clear purpose, strategy, goals and objectives for change

- build a change team

- lead change (create reasons for change, enlist your stakeholders, and identify new behaviours and habits to support and reinforce change)

Introduction

The demands of today’s volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) environment are placing extraordinary pressure on program directors. There has never been a more demanding time to lead, as we grapple with a health care world that is rapidly evolving. This transformation is being driven by many trends, including economic pressures, demographic changes, incorporation of equity, diversity, inclusivity, and accessibility (EDIA) principles, artificial intelligence and technology shifts, all of which call for greater innovation, yet often with less resources and financial support. To manage the flux that we’re facing in our workplaces, we need to be prepared and equipped to lead change. This chapter briefly describes key change leadership strategies that you can employ in your role as program director (PD). The goal is to equip you with the skills, practices and confidence you need to be an effective change leader.

Where to start: build the foundation

At one or more points in your tenure as PD, you will probably be faced with the challenge of knowing something needs to change but feeling overwhelmed at the prospect of having to figure what needs to happen and how to do it. Implementing change is more art than science. There is no one model that is guaranteed to work in every situation. As a PD, your real work in leading change is about making sense of a complex situation to identify the elements that will make the most significant contribution to effecting change. Leading change is about being willing to assume leadership, building teams and trusted relationships, finding compelling reasons for change, mobilizing others, and being willing to start the change process and then adapt as everyone learns, all while under pressure and discomfort. Even though leading change — particularly complex change — in medical education is challenging, it’s a noble cause: there is no other way to improve the education we provide to future physicians, and it will make our medical cultures and organizations better. As change guru Peter Block said, “the price of change is measured by our will and courage, our persistence, in the face of difficulty.”1

It is not easy to implement change in residency programs. Postgraduate medical education is a nonlinear complex system that interacts with many other components of an academic health care system, ranging from community clinics to tertiary care hospitals to national governing bodies, with many other institutions in between. These organizations may operate in silos, with differing cultures, values and beliefs. Implementing change that can have a lasting effect across all these domains can seem daunting — but it is possible. If you take a structured approach, you will help not only yourself but also the people who look to you for direction and support. A structured approach is a key ingredient for success — without it, most change initiatives fail. The next section will set out some of the key practices most associated with successful change processes, which you can employ as you structure your own change process.

Lead the way from within your program

As a change leader, you will have to provide active and strong leadership/sponsorship throughout the entire change process: you will have to provide reasons for the change, assess the potential impact of the change you are proposing, engage stakeholders and then communicate clearly with them throughout the process, ensure that everyone is clear on what needs to be done and is working with the same objective(s) in mind, provide coaching and support, and manage through reactions of stakeholders. The leadership gap, which can be defined as the gap between the leadership competencies that leaders currently have and the ones they need to lead effectively, is consistently cited as the biggest barrier to successfully implementing change within organizations. Leading change requires more than subject matter knowledge and technical expertise. It requires the capacity to deal with interpersonal, relational and group dynamics.

Define the change

Prior to embarking on a change process, it is crucial to have defined the issue and have a systematic approach to choosing potential solutions. Now, as you embark on a change process itself, the first step is to define the change that you’re envisioning. Can you make clear the change that needs to happen? Why it needs to happen? Who it is going to affect? How it will improve your program? Whether it will provide additional benefits outside your program? Imagine yourself on an elevator with one of your colleagues. You have this great idea you would like to implement for your program — can you quickly articulate exactly what it is you would like to change before your colleague gets off on the next floor? Once you have a good understanding of the change you would like to implement, then you can start to build your team.

Build and lead a cohesive team

Successful change can require mobilizing large numbers of people toward the vision of an improved future. This important relational work facilitates readiness for change while addressing the perspectives, priorities and needs of the large number of individuals and groups who have a stake in the change. Start small, and then attract and connect a team of people by building relationships and creating clarity. Don’t go it alone. A good place to start enlisting your team is to find your innovators and early adopters. Every program has them — you just have to look for them. Work with these people rather than pushing against those who are not yet ready to adopt and have higher resistance levels. Additionally, look to enlist those who may be most affected by a proposed change – they likely have perspectives that may be missed if you focus on those who are less affected. In later stages of change, having team members who are highly affected by change (i.e. lived experiences in EDIA language) contributes to better solutions and a greater chance of buy-in by highly affected groups.

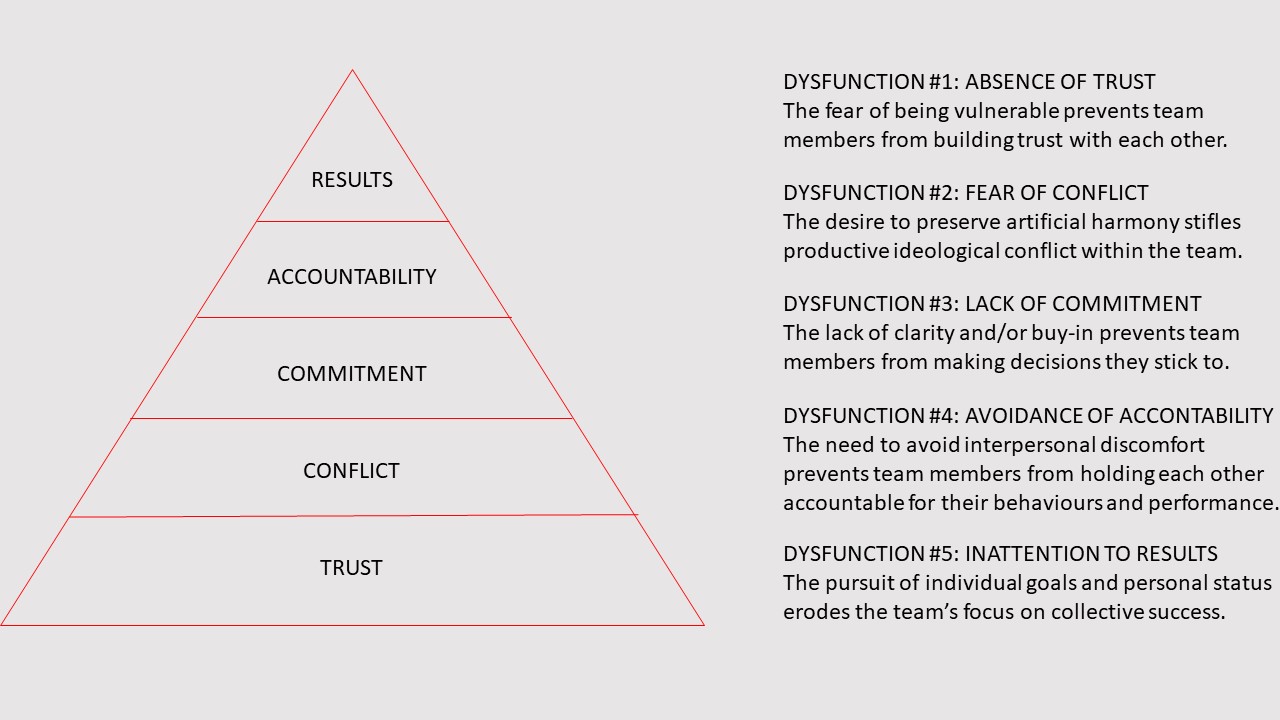

Patrick Lencioni, one of the leading authorities on team development, defines a team as a small group of people who are collectively responsible for achieving a common objective for their organization.2,3 The size of the team matters; he recommends that teams should be made up of three to 12 people to maximize their effectiveness. A key component of team effectiveness is the quality of communication that results from balancing advocacy and inquiry. Lencioni’s model for team effectiveness sets out five factors that cohesive teams embrace (Fig. 14.1).4 These are all cumulative.

- Trust – Trust is a precondition for change and makes teamwork possible. People need to trust in change leaders to follow their change agenda. Leaders often overestimate support. When you are making a change in your residency program, it is your role as PD to create a safe environment in which your team members can be vulnerable. Particularly in situations where traditionally underrepresented individuals are giving their perspectives or lived experiences that may not be experienced by the majority of the team. The only way you can do this is to model and lead the way by being transparent, admitting your own weaknesses and mistakes and asking for help. When teams build trust they are more able to engage in productive conflict by including and exploring differences and working toward common solutions.

- Conflict – To encourage your team to engage in more healthy conflict, it is helpful to establish rules of engagement. Declare that silence during discussions will be interpreted as agreement. This will encourage people to weigh in to ensure their perspectives are heard. It is also imperative that you recognize when conflict alienates those who are marginalized, especially when making change in EDIA topics. Keeping in mind who’s voices and opinions are easily heard and centered in a conversation may help you to realize that valuable perspectives may be lost. As the change leader, it is up to you to steer the conflict to “centre the margins” in the safe environment of trust you’ve created. Healthy conflict helps teams to achieve commitment.

- Commitment – Commitment can only happen if people are provided the opportunity to share their perspective. If people don’t weigh in, they can’t buy in. At the end of every discussion go around the room and ask every member of the team for their commitment to a decision. Note that this is not about reaching consensus: it is possible for people to disagree and still commit to the decision. Rather, once everyone has been heard, you can then make a clear decision so that everyone walks away understanding what agreements have been reached and what specific actions will be taken next.

- Accountability – You and your team members need to hold one another accountable to commitments and actions. You can then review these commitments in one-on-one and team meetings.

- Results – Once your team has established trust, made commitments and established accountability then team members can work on collective priorities and achieve results.

Figure 16.1: Lencioni’s trust pyramid: the five behaviours of a cohesive team.

Lencioni P. The advantage: why organizational health trumps everything else in business. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2012. Reprinted with permission.

Early in the Change process

Why change is hard and how to move forward

In speaking with PDs across the country about the challenges of implementing change, such as the transition to Competence by Design, the issue they have most frequently raised is difficulty with engaging faculty, residents and other key stakeholders. This is inevitable —attempting to transform the daily behaviour of people is no simple task. Atul Gawande, in his book Being Mortal, quotes Dr. Bill Thomas: “Culture is the sum total of shared habits and expectations … Culture has tremendous inertia. That’s why it’s culture. It works because it lasts. Culture strangles innovation in the crib.”6

We know from neuroscience and psychology that we are wired to resist change because it requires us to replace our trusted standard operating procedures with new behaviours and habits. This is very taxing for our brains, which are ruled by two different systems, the rational and emotional, which often have competing needs. As Chip and Dan Heath said in Switch: How to Change Things When Change is Hard, the rational mind wants a great beach body and the emotional mind wants an Oreo cookie.7 When a change comes along, most people who hear about it might agree that it is the right thing to do and may see the value of the vision — this is the rational mind response. However, the rational mind can also overanalyze, get paralyzed by uncertainty, and see threats and problems everywhere. In the meantime, the emotional mind is freaking out because it loves the comfort of the status quo and can’t imagine how it will find the time to change and adopt new habits and activities. These two streams of discomfort can overwhelm any change initiative. Now imagine a department full of individuals hardwired to resist change. Overcoming their resistance is going to take a bit of strategic planning and persistence.

Recognize and normalize the dip

The path to a new way of doing things rarely follows a straight line. Change can be messy. Expect that there is going to be a “dip” along the way that can feel like a threat; it might include stress, disruption, fatigue, discomfort and setbacks. The journey to change usually takes longer than we’d like. It’s natural for there to be tension as people adapt to change and make it their own. As soon as you begin a change initiative and articulate a vision for a new future you have already created difference and possibly tension, discomfort and conflict. At some point in the change process you might be confronted with a different perspective (either from a person with whom you’re talking one on one or from a room full of stakeholders) — it’s natural to react to this and feel a sense of loss that can rock your self-image. But don’t let this dip erode your commitment and willingness to change. Hold fast to your belief that change is necessary, even if the way you go about this change may differ based on others’ perspectives. In leading change, you need to be able to wade into discomfort and vulnerability. As Brene Brown says, “Vulnerability is the birthplace of innovation, creativity and change” 8 — hopefully in an environment that feels safe and does not take you too far outside your comfort zone. If you and your stakeholders are not uncomfortable, you are probably not changing. This is especially true when reflecting on changes related to EDIA. Through recognizing our own feelings of discomfort in our personal role in racism, gender discrimination, transphobia, etc., we can help focus on the elements that will make the greatest positive difference. A key role for you as a change leader is to build your own resilience and guide others to navigate the changes in a sustainable way, with persistence and energy.

Cooperate with the way people change

So how can you overcome the discomfort and resistance of your stakeholders and move forward? In Diffusion of Innovation, Everett Rogers says that an idea for change will not be embraced by everyone at first.9 Rather, the change will initially be embraced by a small group of innovators and early adopters who will start small, practise new behaviours and make their progress and learnings visible (Fig. 14.1). Robert Cialdini offers more practical tips in his book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, describing six principles of influence.10 He shows that we are all influenced by those around us. Over time change gains momentum and spreads more widely as the early adopters show their progress and others join the movement, not wanting to lose out. Once enough individual adopters have joined in, your change process will reach critical mass and the innovation will be self sustaining. For any innovation, some people will be late to join; you do not need everyone to adopt your change at the beginning. Be selective in who you recruit at the outset, and focus on achieving critical mass of adoption. The rest of your department will follow once you reach this point. Derek Sivers’ “Dancing Guy” video is a fun way to walk through the leadership change process.11

Involve people throughout the process of change

Change is not a linear process; it is more like white water rafting than rowing in a regatta. As you implement change, you will often take two steps forward, one step sideways, and one step back, make mistakes and encounter obstacles, risks, discomfort, disappointment, misunderstandings and vulnerability. No changes are immune to this reality. Change is often referred to as something you “roll out,” and we all use terms that imply control — we assume that somehow we are the drivers and managers of change and think it will happen our way and on our schedule. In fact, most changes are not accomplished in a one-time roll out but rather through multifaceted efforts that may evolve over time.

For instance, when began to roll out in Canada, the Royal College and community of change makers including the PDs, learned that the real work is to involve people to build readiness to change and co-create shared solutions. Capturing the minds and hearts of intelligent people comes down to a few simple (but not necessarily easy) things. It gets messy, especially if you want to make change happen on your own set timeline.

Ultimately, it’s all about involving people to determine how the change is going to work. People own and support what they help to create. This is at the heart of change. Nothing empowers people more than being involved and having a say in how the change can be done. This can be a simple as you returning from a Competence by Design workshop led by the Royal College and saying, “As we implement Competence by Design in our program, here are the three key things we are required to do to meet the standards. Who would like to be involved to figure this out for our program?” Invite people to evolve the idea and give them room to create the best solution for their unique context.

Facilitate reasons for change

A vital part of leading change is to help others to find their reasons for change. To do this, you will need to take an iterative approach to framing and reframing key themes that capture the attention of others — themes that resonate and that people care about will motivate them to support the change with shared purpose, drive and passion. Data and intellectual appeals are necessary but not sufficient. You also need to share stories that generate emotional energy and critical self-reflection, provide important examples of what works and how to overcome challenges, build confidence in your team’s ability to make change happen and mobilize people to do what is possible based on what matters to them. Nothing influences people more than seeing how trusted peers achieve results.

As early adopters in your program start to make progress and learn valuable lessons, make sure you make their success visible. Publicly share the first small successful steps toward change. Cialdini calls this “social proof.” 10This is a key strategy that will enable your team to clone or copy successes and light a spark that will spread throughout your program. People do not want to be left behind and miss out on success. Dr. Rob Anderson, a previous PD of Anesthesiology at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, said this about the experience of transitioning to Competence by Design: “We shared every success. We tried to make it about the program and others involved. No achievement was too small not to celebrate. We were creating a brand new program and I wanted my team to be excited.” Success is contagious. Everyone loves to hear positive outcomes, so don’t forget to celebrate the small steps as you continue on your change journey. However, it is key to remember to balance celebrating success with humility and an ongoing recognition of work that remains to be done. For example, while it would be a success to implement an Indigenous health curriculum for residents, this is one step in a much larger process. Acknowledging the work still to come can overcome concerns, particularly in EDIA-focused work, of virtue signalling. Also, consider highlighting the work of a team member or leader with lived experience as a method to contributing to equity, with their permission.

Getting into action

Identify new roles, actions and habits to create change

In the early stages of your change process, you will be spending a lot of time making decisions about what the change is and how it will be implemented. As the change progresses, you will need to pivot to establishing clear roles, behaviours and habits. These are just as important to the success of the change as your program’s resources, structure and systems and your change strategy. Establishing new ways of doing things can take some practice, learning and adapting. Organizational culture is just a collection of habits. Help people in your program to ask “What is my role in this change?” One of your key roles as a change leader is to help everyone involved to identify and practise new behaviours and build new habits. This will take time and feel uncomfortable, and it will require some experimenting.

When it comes to changing behaviour, less is more: identify one new behaviour to start or stop at a time. Try out the new behaviour and learn from what happens. Some experiments will be a waste of time and others will lead to some positive results. Identify what action you will take and how you will assess the results. Commitment to new behaviours develops over time; it occurs as experience is gained and lessons are learned.

Keeping in mind our insights from Rogers’ diffusion of innovation9, start with a small group of the ready, willing and able, and identify specific actions for this group to take. The rational mind can be inspired by the long-term vision and follow an action plan. But don’t expect people to change just by hearing about lofty goals, visions and documents; you will have to work together with them to identify practical everyday actions. For example, as Dr. Steven Katz, said Competence by Design is about spending two or three minutes a day with your resident where you focus on one thing that they can do better.12 Major change will happen as a result of the aggregation of lots of small changes made by many people consistently over time that will collectively generate unstoppable momentum. The simplest way to generate this momentum is to determine what activities each stakeholder must engage in every day, week, month and year and then encourage them to practise them.

Communicate early and often

Once you have established your leadership role, defined the change, built your team, identified your early adopters, helped everyone to find their reasons for change, and established clear roles and behaviours, remember to communicate continuously during the change process. There is no such thing as too much communication; in fact, many problems can be traced back to poor communication. Consider who is the best person to deliver each message. As noted earlier, people are influenced by their peers and so it is crucial to engage peer champions in enlisting and mobilizing others as trusted communicators and influencers. You will also need to strike a balance between communicating plans and details of the change as well as create opportunities for face-to-face interactions including coaching and supporting people through .

Embrace change with a growth mindset

Expect setbacks: they are a natural part of any change process. Change takes time and will involve some missteps. Model how to handle setbacks, and help people stretch and grow to be bigger than the challenge. Do this by approaching hurdles with curiosity, starting small, trying things, taking in feedback, learning and adjusting. The change process is a U-shaped curve. You will start with a compelling vision and will hope to arrive at a positive future. Everything in the messy middle is change, growth, learning and adaptation. Implementing complex change can involve many hurdles that can test your team’s commitment and can make people forget their common purpose to improve medical education. A good mindset for change can help you to overcome challenges and navigate choppy waters. Cultivate a beginner’s mind (a state of mind in which you are free of preconceptions about how things work, filled with curiosity and open to possibilities) and embrace experimentation. Changing a complex human system such as medical education is an adaptive challenge. This means your first iteration is probably not the best, so be willing to quickly let go of what is not working effectively. Be curious and invest time in trying to identify the patterns that make a positive difference. Indeed, after multiple iterations your ultimate design may not look at all as you predicted, particularly as you adapt it to work in unique local contexts. The most important thing is that you are taking a step in the right direction.

Tips

- Share tools and a story.

- Enable people.

- Go for progress, not perfection. Make progress visible for all to see. Celebrate small successes along the way.

- Learn together and leverage learning in your community.

- Act swiftly to remove barriers and address resistance by listening to concerns and working with people to co-create solutions.

- Lastly, remember to have fun!

Conclusion

Don’t go for perfect. Get started. As a PD you will be invariably be faced with the need to change. Implementing change takes time, thoughtfulness and a strategic mindset. Start with early adopters who will take the time to learn about the change, take the risk to try it, take their peers’ time to tell them about it, and model it. Make the change process less onerous by focusing on the elements that will make the greatest difference. Involve others to create the new behaviours, roles and habits. Remember that habits are the building blocks of behavioural change and that all change is behavioural.

Further reading

- Cross J. Three myths of behavior change — what you think you know that you don’t [TED talk]. Available from: youtube.com/watch?v=l5d8GW6GdR0&app=desktop

- Heifetz R, Grashow A, Linksy M. The practice of adaptive leadership: tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Boston (MA): Harvard Business Press; 2009.

- Herrero L. Viral change. United Kingdom: Meetingminds Publishing; 2008.

- Hoopes LL. Prosilience: building your resilience for a turbulent world. Dara Press; 2017.

- Kegan R. In over our heads: the mental demands of modern life. Boston (MA): Harvard University Press; 1998.

- Kegan R, Lahey LL. Immunity to change: how to overcome it and unlock the potential in yourself and your organization. Boston (MA): Harvard Business School Publishing; 2009.

- Positive Deviance Collaborative. Homepage. Available from: https://positivedeviance.org/

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2000-13324-007

- Sivers D. How to start a movement [TED talk]. Available from: ted.com/talks/derek_sivers_how_to_start_a_movement?language=en

- Croix R. Prepare your program for change. In: The meantime guide. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2017. Available from: www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/documents/cbd/full-meantime-guide-e#change

- Croix R. Lead the change [module]. In: Competence by Design for program directors: a practical resource. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; n.d. Available from: https://www.royalcollege.ca/mssites/cbdpd/en/content/index.html#/lessons/Jg3wy9Chb1xV1OHzo1Lf97RoGzq8YS8c

- Weggeman M. Managing professionals? Don’t! How to step back to go forward. Amsterdam: Warden Press; 2014.

- In over our heads & Immunity to Change by Robert Kegan

- Switch by Dan Heath (short videos)

- ACE the steps to change https://www.processexcellencenetwork.com/tools-technologies/articles/ace-the-steps-to-change

References

- Peter Block (2003). “The Answer to How Is Yes: Acting on What Matters”, p.35, Berrett-Koehler Publishers

- Lencioni P. The five dysfunctions of a team: a leadership fable. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

- Lencioni P. The advantage: why organizational health trumps everything else in business. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2012.

- Lencioni P. Discipline 1: build a cohesive leadership team. In The advantage: why organizational health trumps everything else in business. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2012.

- Stephen M R Covey, Speed of Trust

- GawandeA. Being mortal: medicine and what matters in the end. New York (NY): Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company; 2014.

- Heath C, Heath D. Switch: how to change things when change is hard. New York (NY): Crown Business; 2010.

- Vulnerability Is the Birthplace of Innovation, Creativity and Change: Brené Brownat TED2012,” TED Blog, March 2, 2012, https://blog.ted.com/vulnerability-is-the-birthplace-of-innovationcreativity-and-change-brene-brown-at-ted2012.

- Rogers E. Diffusion of innovation. 5th ed. New York (NY): Simon and Schuster; 2003.

- Cialdini R. Influence: the psychology of persuasion. New York (NY): Harper Business; 2006.

- Sivers D. First follower: leadership lessons from dancing guy. Available from: https://youtu.be/fW8amMCVAJQ

- Katz https://www.royalcollege.ca/rcsite/publications/cbd-community-touchpoint-e

- Heimans J, Timms H. New power: how power works in our hyperconnected world — and how to make it work for you. New York (NY): Knopf Doubleday; 2018.