Objectives

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- plan educational activities following the five steps of educational design

- describe how starting with clear, well-defined program outcomes helps with curriculum planning

Case scenario

Dr. Tremblay is the program director of a large anatomical pathology residency program with 20 residents. He has been noticing that some of the residents are not progressing on a particular core entrustable professional activity (EPA), “presenting cases at multidisciplinary cancer conferences.” To gain a better understanding of the issues, he takes a look at the ePortfolio dashboard and realizes that there are very few observations in which the residents were entrusted to perform this EPA, even at the end of the core stage. Because this pattern is only evident for this EPA, Dr. Tremblay believes that the residents are performing poorly because they are struggling with communicating with clinical colleagues or on presenting to a multidisciplinary audience. He decides to do something about this. He invites a colleague, Dr. Nguyen, who is known to effectively represent pathology at tumour boards, to brainstorm over a cup of coffee. He tells her about his initial plan, which is to invite someone from the faculty development office to give a workshop on communication skills and to invite Dr. Nguyen to give a lecture on how to prepare for and present at tumour boards. After a short silence, Dr. Nguyen asks, “Do you know why they are getting low ratings?” She continues, “If your diagnosis is wrong, you will give a treatment for a disease that doesn’t exist, and their symptoms will persist.”

Introduction

What is the desired outcome of the activity that you are planning? Whether it is a problem that needs fixing, a new EPA, or a goal to be achieved, the most important aspect of designing an educational activity is to begin with the end in mind. In the competency-based medical education (CBME) era, desired outcomes should be expressed in terms of measurable behaviours, well-defined abilities that learners will be able to demonstrate as a result of learning.1,2 In the case scenario, the desired outcome is not high ratings in an EPA but rather the ability to represent pathology at tumour boards. With the desired outcome in mind, you can identify the real issue, refocus and determine a path to achieve the end goal.

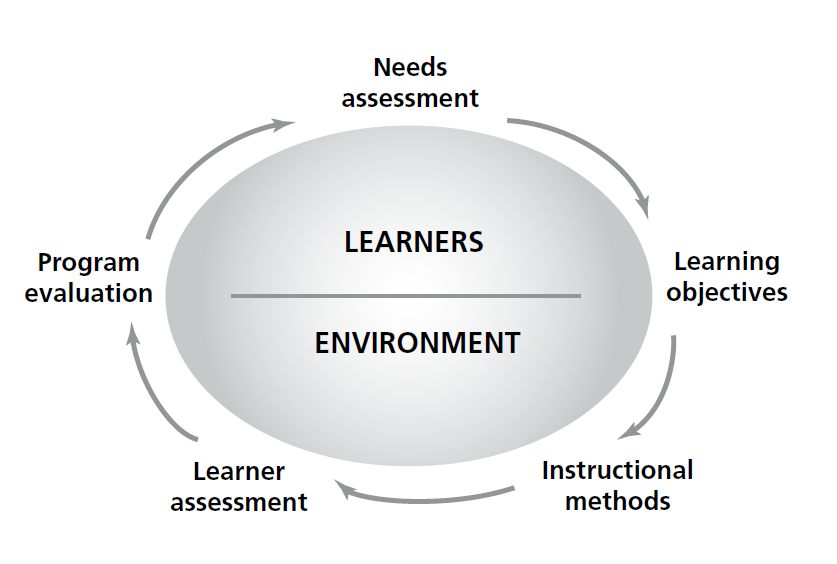

The five steps of educational design1 can be applied to address various educational needs that you will encounter as a program director.1 For example, they can be used to prepare a one-to-one clinical encounter in the workplace, design a single educational activity, organize an academic half-day, create a new clinical rotation or restructure an entire residency program, as in the implementation of Competence by Design. Regardless of the type of educational activity you are trying to create or improve, you first need to identify and understand the issue you want to address. What is the outcome that you are trying to achieve? Is there a (real) problem? If so, what is it? Is it a problem worth devoting your limited resources to (time being a big one)? Will an educational activity help you fix the problem or achieve the desired outcome? Once you decide to attack a well-defined educational goal, the five steps provide an effective process to achieve your goals.

The five steps of educational design

1. Conduct a needs assessment

If you have decided that an educational activity is a good treatment for the problem you have identified, it is because you have established that your learners’ performance can be improved by working on their knowledge, skills or attitudes. You now need to understand why their performance is subpar or what are some new abilities that they need to develop. Given your expertise, you might have a good idea just by looking at the situation and the symptoms, but you still need to take a history, perform an examination and maybe order some tests or discuss with a colleague to make sure you have correctly identified the cause of the problem. As illustrated in the case scenario, if you make the wrong diagnosis, you will prescribe the wrong treatment and you will not achieve your desired learning outcome.

There are many tools and strategies that you can use to identify specific learning gaps. Given that people are not reliable at assessing their own performance, it is a good strategy to look for external data first, such as expert opinion (you can talk to your colleagues) or markers of performance (quality indicators, previous assessments, chart audits).1,3 You can also assess your residents’ performance as it relates to the problem at hand using tools such as a multiple-choice questionnaire or multisource feedback. The advantage of assessing your residents’ performance is that it will help you sort out whether the problem is a matter of knowledge, skills, attitudes or a combination thereof.1,3

Finally, it is essential to ask for the learners’ input. Gauging their perspectives regarding the problem will not only provide face validity to the process but more importantly will help you to gain insight into their attitudes, the hidden curriculum and the learning environment. You can do this using questionnaires (e.g., electronic surveys) or focus groups. Whatever tool you choose, it is important to get expert assistance. The postgraduate medical education (PGME) office or department of medical education at your institution is a good place to start.

It is also key to recognize that some residents may not perceive a problem to begin with, particularly when it hasn’t affected them directly. For example, non-BIPOC (black, indigenous, person of colour) residents may not recognize the extent that racism within the healthcare system affects their BIPOC patients and colleagues. As such, targeted engagement with residents or communities is often important when gaining insight into issues focused on equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI). Also, reflecting on your positionality to an issue (e.g., a straight cis-gendered PD approaching a concern about LGBTQ+ care) should lead you to partnering with others who may be more knowledgeable and/or have lived experience.

2. Create learning objectives

Once you have defined the problem and identified the learning gaps that need to be addressed, put into words what your learners will be able to do after they complete the educational activity that you are planning: these are the learning objectives. Ask yourself or your team: If the learners acquire these competencies, will the problem be solved? Learning objectives must match the needs and be very specific. Focus not on what the teachers want to teach but on what the learners need to learn. Learning objectives must be determined by curriculum developers and provided to the facilitator of the educational activity.

An acronym that is commonly used to develop learning objectives is SMART: learning objectives must be specific (they must address the particular learning gap that you have identified), they must be measurable by some sort of assessment (that you will create), they must be achievable by the learners with the available resources (taking into consideration the magnitude of the learning gap and the availability of time, funds, space, people, etc.), they must be relevant to the initial problem and the program’s goals (will the educational activity fix the problem?), and they must be time bound so you know when to expect the results (e.g., at the end of a lecture, series of workshops or entire rotation).4

Depending on the needs, learning objectives might target different domains (cognitive, psychomotor or affective). They should be conceived in a progressive manner to provide scaffolding for learners to achieve higher order skills as the educational activity unfolds. Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives is one of the most commonly used conceptual frameworks to write objectives in a sequential manner, from factual knowledge and understanding of concepts to application in problem solving and analysis of real or simulated scenarios, according to the developmental stage of the learners.5 The taxonomy proposes a list of action verbs that should match the ability that you want your learners to develop after going through your educational intervention.

3. Choose instructional methods

One of the most common (but inappropriate) practices in educational design is to start the planning process by defining the instructional method, which typically is a lecture by default. This is not surprising, because lectures allow instructors to deliver information; they are familiar to teachers and learners; they are easy to prepare, deliver and attend; teaching rooms are usually set up in theatre style; lectures require few resources and the logistics are straightforward; it is easy to assess learners and to evaluate the intervention; a number of checkboxes can be checked effortlessly (accreditation, to-do list, your conscience, etc.); and delivering a lecture will surely decrease your anxiety by giving the impression that you have addressed the problem. But if learners attend a lecture, will their needs be fulfilled, will they develop the abilities you described as your learning outcomes, will their performance change and will the problem that you identified be fixed? In most cases, lectures are an over-the-counter treatment of symptoms that will not address the underlying cause of the problem. Also, they are not the best use of your teachers’ highest value (experience) or most scarce resource (time)! Information is now widely accessible, and the primary role of teachers is to use their practical expertise to facilitate knowledge translation and coach trainees, not to deliver information.

Instructional methods need to match learning objectives that in turn address the needs of the learners, so that learners’ performance is changed and the problem is solved.1,3 At first glance, it seems like choosing instructional methods should be simple, but it is important to enlarge the instructional palette of your program and vary your tools.1,3 For factual knowledge, reading a text or watching a tutorial might do the trick; for comprehension, a flipped classroom or interactive lecture will probably suffice; for application, you might need a case-based discussion or role playing; psychomotor skills will probably be best addressed by simulation exercises; and for attitudinal change on a sensitive matter at the workplace you might need longitudinal coaching. A number of resources are available to help you determine the most appropriate method to meet your objectives.1,3 Your local faculty development and PGME offices are invaluable resources to assist you in the application of new methods.

As you start to follow these steps, you might realize that you will require a number of spaced and varied educational interventions to fix the problem. You may initially have thought you were a lecture away from redemption, only to find out that you need to embark on a journey to get to the promised land. But do not get discouraged. Squeezing unrealistic objectives into a one-hour unidirectional, unimodal and passive teaching session has unfortunately been ingrained into educational practice since the first lecture ever, but effective education is the product of a well-designed and deliberate process. And you are the project manager.

4. Assess learners’ performance

In education, the term assessment refers to the assessment of individual learners (compare this with the term evaluation in the fifth step below). There are a variety of assessment methods and instruments available, but in essence all of them try to answer the same question: Are the learners able to demonstrate the desired learning outcomes/competencies? Therefore, your assessment methods need to provide a measurement of learners’ achievement of the specific learning objectives of the activity: factual knowledge and comprehension can be tested with multiple-choice questions or short-answer questions, application of knowledge can be evaluated using oral examinations with case-based discussions, psychomotor skills might be observed on simulation exercises, assessment of communication and collaboration skills will be better achieved from multisource feedback, and performance of an entrustable professional activity (EPA) from beginning to end usually require observation in the workplace.6 Once again, you will probably need to broaden your assessment palette, and you might need to mix and match different methods depending on the learning objectives of the activity, but you will not need to reinvent the wheel. There are easy-to-follow guidelines that will help you to find the right assessment methods and make your task less daunting.6 As per the advice given for the needs assessment, this is another important opportunity to consider the positionality of the assessors of a resident’s performance and how this may impact assessment.

The science of assessment is broad and complex, but there are some general principles that can be applied to any assessment situation. One of the frameworks used is CARVE:7

- Cost: What effort and resources are required for the enterprise? (Remember to account for the time it will take.)

- Acceptability: Is it acceptable to learners, teachers and other stakeholders?

- Reliability: Does it provide the same results on repeated measurements?

- Validity: Does it measure what it is intended to measure?

- Educational impact: Does it help solve your problem?

With the Canada-wide implementation of Competence by Design (CBD) in PGME, workplace-based assessment (WBA) has become a cornerstone of any program of assessment.2 WBA requires the observation of residents’ performance while they are performing EPAs. These observations are opportunities for supervisors to use their experience and expertise to coach learners so they can progress to their next developmental stage. This ”assessment for learning” strategy is primarily an instructional method, but there is a component of low-stakes assessment. As you collect a large number of these small biopsies of performance, you provide robust evidence for the competence committee to make a decision on each resident’s achievement of competence. Therefore, it is important to train supervisors and learners on how to perform and document WBA (i.e., invest the required resources and engage stakeholders), to ensure that your supervisors are assessing the right thing in the same way (i.e., the assessment will be valid and reliable) and that learners will benefit as much as possible from the clinical encounter (i.e., the educational impact of the encounter will be maximized).

5. Conduct a program evaluation

In education, the term evaluation usually refers to the evaluation of an educational activity as a whole, whether it is a lecture, a rotation or an entire residency program. Once again, regardless of the activity you are trying to evaluate, you will be trying to respond to the same basic questions: Did it work? Why or why not? What worked well? What could be improved?

In terms of the first question, the most commonly used framework to evaluate the educational outcomes of an activity is Kirkpatrick’s framework of learning outcomes or one of its adaptations:8

- Did learners like it? (They came, participated and were satisfied.)

- Did they learn? (Their knowledge, skills or attitudes improved.)

- Did they change their behaviours? (They applied their new skill set in real life.)

- Has it improved patient outcomes? (Their improved behaviours translated into better care.)

Although every component is important and they are all interrelated, it is difficult to determine whether patient outcomes, or even behaviours, have changed as a direct consequence of a specific educational activity. Furthermore, the effort required to demonstrate this is usually undertaken as part of a research project and is not part of the daily job of a program director. Therefore, it is usually appropriate to create well-designed evaluations that focus on learners’ satisfaction and learning. It is worth noting though that some educational activities, such as cultural safety or anti-racism training, purposefully move people out of their comfort zone as part of the experience. This is done because the discomfort often fuels self-reflection and eventual behavioural change. As a result though it is important to engage a skilled facilitator in these circumstances. They may be better able to evaluate the connection between discomfort and possible lower ratings.

To get a better picture of your educational intervention or program, it is important to use the lens of continuous quality improvement. Looking solely at the outcomes is not going to help you understand and fix what is not working well or improve your already successful strategies. For instance, if the learners’ performance did not improve, it might be because the instructor did not have sufficient time to prepare the session, the learners did not attend the session or the assessment method was inadequate. The logic model is one of many approaches to program evaluation.4,9 It allows you to take a snapshot of your program and determine where you want to focus your evaluation and improvement initiatives. It looks into the following elements:

- Inputs: the available resources, including time, personnel and equipment

- Activities: all planned activities, including advertising, educational sessions and evaluations

- Outputs: all activities that actually took place, including the timing and type of advertising, the number of people who participated in the activity and the number of people who completed the evaluations

- Outcomes: short-term and long-term, including intended learning outcomes as in Kirkpatrick’s framework, and unintended outcomes

Mapping out your educational activities in a logical manner will help you to plan, implement, evaluate, improve and advocate for your program.

The program evaluation closes the five-step cycle of educational design and helps you to prepare for the following cycle. In essence, it will go backward through the educational design process and ask the following questions:

- Are we able to demonstrate that the learners achieved the desired learning outcomes?

- Was the instructional method designed to address the learning objectives and delivered as planned?

- Were the learning objectives specifically developed to address the learners’ needs?

- Were the needs of the target audience clearly identified and relevant to the original problem?

- Have we fixed the problem? If not, why not and what’s next?

Figure 5.1

Sherbino J, Frank JR, editors. Educational design: a CanMEDS guide for the health professions. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons; 2011.

Tips and challenges

Tips

- Focus on the end goals or the actual objective, not the mean goals or the steps and activities you need to take to get you to the end goal.

- Make a proper diagnosis before embarking on a resource-intensive journey.

- Mind the gap. No educational activity is effective in and of itself. It involves a dialogue with the audience. The lack of a proper needs assessment is at the root of most (and the most) ineffective educational activities.

- Assess your assessment and CARVE out a solution.

- Collaborate, do not reinvent, be logical and passionate.

Challenges

- Time (yours)

- Time (your coworkers’ and residents’)

- Time and time again

Conclusion

The five-step process of educational design is an effective way to achieve your desired learning outcomes. But it is a process, and like any other process it requires time to be perfected: not time in terms of the natural passage of months and years, but time in terms of the number of times you apply the process and as a resource that you invest to design, implement, evaluate and reflect on the program and the process itself. Think big, but start small. If you are new to the game, begin by conducting a needs assessment, trying a different instructional method or using a new assessment instrument, and build up your skills. Canada is blessed to have a large number of qualified clinician educators, and there is no doubt that you will find a resourceful community at your institution that can mentor you. As you negotiate, manage and invest your most precious resource, the process of conducting proper educational design will eventually become a routine for you, and you will embark on a virtuous cycle that will pay dividends: your program will improve, less remediation will be required, your faculty’s skills will grow and so will yours, you and your team will feel confident and engaged, new career opportunities will arise, and so on. Begin with the end in mind and enjoy the ride!

Further reading

- Sherbino J, Frank JR, editors. Educational design: a CanMEDS guide for the health professions. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons; 2011.

The basics. This step-by-step guide to educational design expands on each of the topics covered in this short chapter. It provides very practical tools and elaborates on their specific indications, contraindications, advantages and disadvantages. It also includes an entire section on implementation.

- Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY, editors. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

A classic. It sets out the approach known as the Kern’s cycle and includes implementation as one of the steps of educational design. It provides a slightly different perspective that will help you shape your own.

- Van Der Vleuten CP. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ. 19961(1):41–67.

A dive. In this seminal paper, Van Der Vleuten introduces, describes and discusses his conceptual framework of assessment that includes the five components of the CARVE acronym. Although somewhat denser than the other resources, it is a good follow-up for those wishing to do a deeper dive on assessment after reading educational design books.

- Kellogg WK. Logic model development guide. East Battle Creek (MI): W.K. Kellogg Foundation; 2004.

A tool. The Kellogg’s guide is an invaluable resource for beginners who want to start using the logic model to plan, implement and evaluate educational activities. It is a one-stop shop: at the same time thorough and practical, it will become a favorite on your bookshelf (physical or virtual).

- Van Melle E. Using a logic model to assist in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of educational programs. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1464.

A page. Once you become familiar with the logic model, you will probably hang this one-pager on your wall and consult it often while designing on the fly or reminding yourself of the big picture.

Case resolution

Dr. Tremblay decides to unpack that EPA and look into the individual assessments. Unfortunately, there are very few narrative comments about the learning gap and almost no improvement suggestions. He decides to organize separate focus groups with residents and supervisors to better understand the problem. He learns from residents that they are not getting feedback after presenting at tumour boards, while supervisors say that residents do not know how to tailor their presentation to the specific audience, giving too much pathology detail and information that is irrelevant to decision-making. It seems to Dr. Tremblay that the best antidote is to train staff on how to coach residents. In consultation with Dr. Nguyen, he decides to pilot mandatory tumour board briefing and debriefing sessions for residents at the core stage. They start collecting multisource feedback to assess residents’ performance at tumour boards. Dr. Nguyen facilitates a faculty development workshop including demonstration, case discussions and role playing. At 3 months a follow-up session is organized for sharing best practices and challenges, and at 6 months a program evaluation questionnaire is sent to residents and supervisors. Dr. Tremblay cannot wait to analyze the responses and correlate the multisource feedback results with the EPA ratings from the dashboard.

References

- Sherbino J, Frank JR, editors. Educational design: a CanMEDS guide for the health professions. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons; 2011.

- Frank JR, Snell LS, ten Cate O, Holmboe ES, Carraccio C, Swing SR, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638–45.

- Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY, editors. Curriculum development for medical education: a six-step approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

- Kellogg WK. Logic model development guide. East Battle Creek (MI): W.K. Kellogg Foundation; 2004.

- Krathwohl DR. A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: an overview. Theory Pract. 2002;41(4):212–8.

- Yudkowsky R, Park YS, Downing SM, editors. Assessment in health professions education. New York (NY): Routledge; 2019.

- Van Der Vleuten CP. The assessment of professional competence: developments, research and practical implications. Adv Health Sci Educ. 1996;1(1):41–67.

- Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J. Evaluating training programs: the four levels. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 2006.

- Van Melle E. Using a logic model to assist in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of educational programs. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1464.