Objectives

At the end of this chapter you will be able to:

- understand the elements of equitable, diverse and inclusive residency program

- become familiar with the impact of the formal, informal and hidden curricula within your program

- develop an action plan to ensure your program operates within a framework of anti-racism/anti-oppression

Introduction

Deliberate Construction of Equitable, Diverse and Inclusive Residency Programs

Residency program directors experience many forces that keep them grounded in the present, or perhaps the near future of weeks to months to a year or two. Examples include: selecting the next cohort of residents; accomplishing a successful accreditation visit; incorporating a new training site into the program; making sure the ICU resident roster is fully covered. These moment-to-moment concerns can weigh heavily.

Residency program leadership must never lose sight of the longer-term goals of residency education, however. Ultimately the raison-d’être of residency education is to train the next generation of physicians in a particular specialty to serve the ever-diversifying populations of the future well. Within a program director’s small part of improving residency education (specialty education of residents), they seek to do their part to build better health care systems and a better world, through greater social justice. They must also be mindful of program responsibilities to learners – to be stewards of welcoming learning environments, where all may flourish according to their abilities, with no barriers to showing their “best selves” in their work and learning, and with their psychological safety assured.

Equity, diversity, inclusion, and an anti-racist/anti-oppressive framework (abbreviated as EDI-AR throughout this text) are key tenets of socially just residency programs.

Definitions

Equity

Fundamental to the concept of equity is the notion of acting with fairness and with a goal of justice (1). It is distinguished from equality in that achieving fairness may not mean equal treatment for all. With respect to the concept of justice, integrated into the concept of equity is that there have been groups of people (e.g., based upon race or gender) who have been and continue to be structurally marginalized within society, and that processes and polices that seek greater equity are fundamentally about addressing those structural issues. Within residency programs, we are asked not to look at institutions within medical education (residency programs, medical schools, teaching hospitals and the like) in the abstract sense as being passive witnesses to the injustices of society, but rather, as fundamental tools or agents in the creation and reproduction of the injustices.

For instance, the forced and coerced sterilization of Indigenous women in Canada, a practice codified in law in several provinces until 1972, and continuing by some counts to at least 2018, was indeed a horrible societal injustice (2). Yet, sterilization is a medical procedure. Graduates of Canadian residency programs performed those procedures. The residency programs taught the paternalistic form of ethics and professionalism which gave rise to the highly troubling justifications for the procedures. For a residency program, perhaps an obstetrics and gynecology program, which is in full institutional continuity with that past, if we continue with the example of coerced sterilizations, the question to be answered is what are the responsibilities in training the next generation, in ways which honour the victims of the injustices and which address the present-day resulting health inequities?

Diversity

On a very basic level, in medicine, populations are defined through one or more characteristics which they share (e.g. Middle-aged South Asian Men at risk for type II Diabetes (this is me!)). Observations about the behaviour of populations are then drilled down to the care of individuals. What, then, is the “diversity” of a population? The diversity of a population simply becomes the socially meaningful characteristics that the individuals within the population do not share. For instance, returning to the example, the South Asian Men might be different by social class, country of origin, sexuality and the like. What differences are socially meaningful depends on the social context. In Canada, we might talk about race, or maybe rurality, among many other qualities that make up the domains of interest with respect to diversity. In India, we might talk about caste.

Another pitfall in the teaching of diversity is to unwittingly ascribe a ‘normal’ within the diversity (e.g. the 70 kg white male that many of us learned about in medical school), with individuals different from this ‘normal’ being presented as ‘deviating’ from it (3). Teaching medical knowledge in this way can be a mechanism through which inequities propagate. With respect to diversity, a key question that residency programs need to consider is how diversity is being represented in what is learned and the diversity of who is present in the learning environment.

Inclusion

Shore et al. have defined inclusive institutional policies from an organizational behaviour perspective (4). Institutions are said to engage in inclusive practices when, through policies and procedure, they simultaneously promote valuing of individuals’ uniqueness and promoting a sense of belongingness for multiple and diverse individuals. What might this look like in a training environment? A simple example might be that in a surgical program, there is a policy for acceptable forms of head covering for Hijab-wearing Muslim residents in the program for work in the operating theatre from an infection control perspective with the policy co-created with major stakeholders (What brands and forms of head covering are permissible). Such a policy would promote both a valuing of uniqueness and a promotion of belonging. For residency training to be inclusive, all policies and procedures must be examined through the lenses of promotion of belonging and valuing of uniqueness.

Framework for examining a residency program for EDI-AR

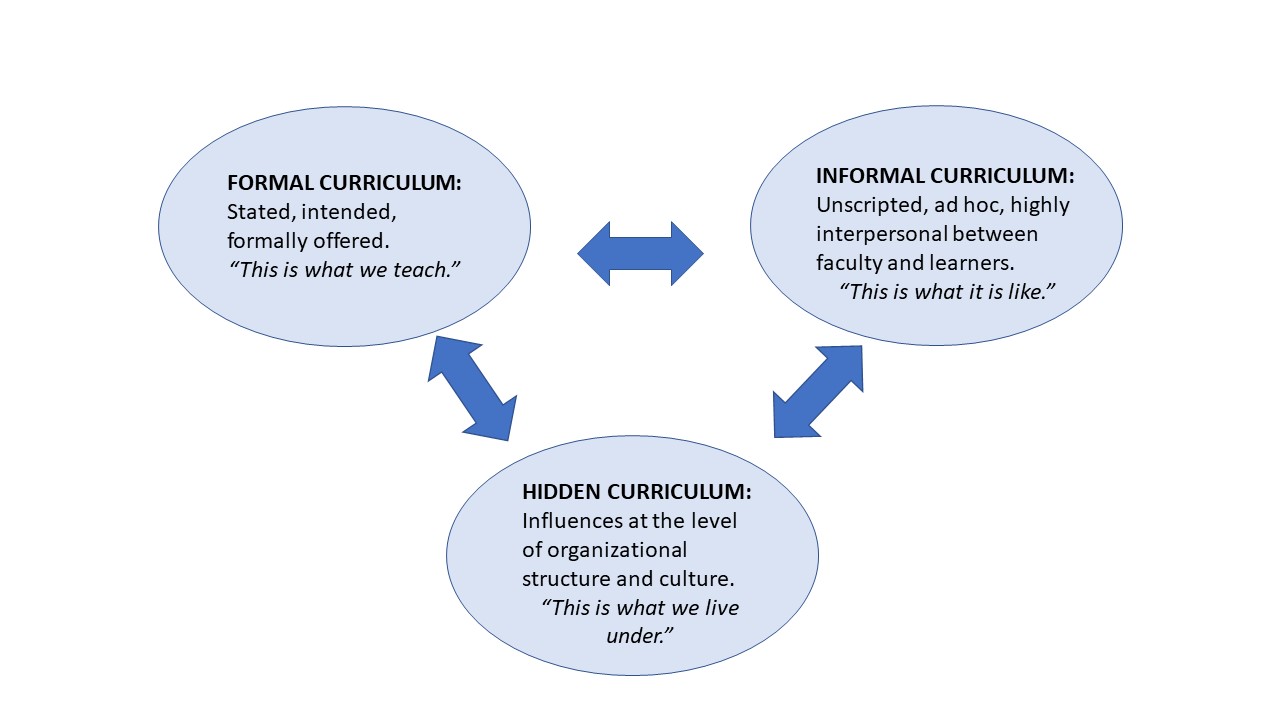

A new program director might ask: how can I embed the concepts of EDI-AR into my program? A useful way to organize deliberate review of a residency program for EDI-AR is the Forms of Curriculum Framework represented graphically below in :

A residency program can be considered as having 3 interacting “forms” of curriculum, the formal, informal, and hidden curricula respectively. As a Program Director, it is key to be aware of all three, and how they impact the program.

The formal curriculum consists of material or training experiences aimed at providing instruction in attaining the stated learning objectives of the program. For a residency program, the formal curriculum includes traditional instructional methods such as lectures and workshops, as might be found in the content of academic half days, but also the required immersive and experiential clinical experiences such as rotations.

The informal curriculum is a similar concept to that of the learning environment, ie. the culture of a learning space (traditional or clinical). The focus in labeling the space as a curriculum rather than the environment of learning emphasizes that educational outputs (behavioural norms etc.) reproduce within it and help perpetuate both its negative and positive aspects, versus a focus on the experiences of learners as is paramount when these informal and unscripted interactions are seen as the learning environment. An example of the informal curriculum would include the learning that might happen on an individual rotation in a particular clinical area.

The hidden curriculum, a term first popularized in medical education by Hafferty and Franks (5), is distinct from the informal curriculum in that it looks at the higher level of how institutional practice is organized. A relevant example of the hidden curriculum interacting with EDI-AR within residency training might be that if a training program holds mandatory teaching sessions between 5 pm and 8 pm weekly on Wednesdays (as a hypothetical example), then this procedural arrangement might unduly affect learners who are parents or caregivers. There is a link between gender and who shoulders the majority of childrearing responsibilities and therefore to EDI-AR.

The formal curriculum

In the vignette above, there are several important elements with respect to the formal curriculum of learning. Firstly, there is the notion of how race, as a form of human difference is being taught and whether that way of teaching is up to date and in line with current scientific consensus (race as a social construct versus a biological construct). Secondly there is the notion of critical engagement skills – for instance the opportunity to teach and discuss flaws in peer review processes with respect to EDI-AR. Finally, there was the missed curricular opportunity to engage in transformative discussion with the learner, other attendees and the attending.

As a Program Director, reviewing formal learning involves deliberate attention to all learning materials and objectives. In the clinical environment, there will likely be a great deal of faculty development as well. Material review and faculty development should adhere to the following:

Key Principles

- Avoid stereotyping (e.g. An OSCE station on substance use, where the patient is Indigenous in origin, perhaps repeated in other settings such as tests etc.)

- Diversity as a fact of life: When diversity variables are introduced ensure that they aren’t only there to highlight a component of the case (for instance, using a case example for pediatric otitis media where the two parents are Mothers, but this fact is not necessary to understand the presenting complaint.

- Use opportunities to examine systemic racism and other forms of systemic discrimination specific to the specialty (for instance, reviewing papers showing differential outcomes by race or Indigenous status for standard surgeries in an anaesthesia residency program)

- Ensure that there are opportunities for critical engagement: Critical race theory, critical disability theory, Feminist analyses of processes of care, and the like.

- Incorporate structurally marginalized patient viewpoints into learning through well compensated narrative sessions where learners learn from patient experiences.

| Action | Target Audience | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct an EDI-AR curricular and rotation review | Program Director, course and Rotation supervisors | Should be checklist driven and with a goal of identifying learning opportunities within content already covered |

| Build capacity among teachers | Program Director, teachers in the clinical environment | Significant commitment of faculty development required. |

| Incorporate New Material | Program Director, curriculum developers, teachers, learners | Critical race theory, Queer theory, Critical disability studies, Feminist analyses of medicine, etc. May require outside expertise. |

| Incorporate EDI-AR into existing structures of educational quality improvement | Program Director, curriculum developers, teachers, CQI experts | Build in an EDI-AR checklist into processes of cyclical review. |

The informal curriculum

Vignette: Dr. Young, a senior cardiologist and division director, comes to your office very exasperated. As the internal medicine program director, you contacted him because a female resident came to you to discuss an occurrence between Dr. Young and herself during her cardiology rotation. He called her a “fine gal” and may have once called her “sweetie” but does not personally remember. The program director said that the resident does not want to proceed through official complaint channels but has given her permission for the program director to speak with Dr. Young.“I was only trying to commend her on her performance during the rotation. I love women. I am not sexist. In the past this would have been a compliment and people just weren’t so sensitive. How is a guy to keep up with changing norms?”

The occurrence described in the vignette is a microaggression. Microaggressions are defined as comments or actions, whether intentional or unintentional, which communicate bias and/or prejudice towards persons from marginalized groups (such as racial groups) (6). In the clinical learning environment, such occurrences often occur within at triad or tetrad. As a triad they might include the supervisor/teacher, who may have committed the microaggression, the learner who received the microaggression, and team bystanders who were witnesses to it. Add in the patient as the recipient of the remark or action, with a learner who socially identifies with the targeted marginalized group, and you have the tetrad. Microaggressions are very common in the clinical learning environment and the subject of much discussion in postgraduate medical education. They have been linked to issues of retention of minority learners and mental health outcomes in minority learners. Along with other forms of mistreatment, they are a fundamental threat to the learning environment. Considering the learning environment as the place where the informal curriculum is transmitted, the key messages of such occurrences are to reinforce social hierarchies – racial, cis- and hetero-normativity, patriarchy, and ableism.

Improving and addressing unwanted parts of the informal curriculum such as microaggressions requires regular and enduring commitment on the part of residency programs. Key components to address are:

| Action | Target Audience | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Build Capacity | Everyone in the learning environment – learners, teachers etc. | Recognition of microaggressions and allyship skills development |

| Collect Data | People and processes within the learning environment | Incidents, with regular and transparent review in the program |

| Ensuring robust systems of Reporting | Everyone in the learning environment | Should be reviewed for whether the process serves the needs |

| Ensuring a principled approach to the learning environment | Educational leadership, teachers, learners | Goal to have principles of a safe learning environment known to all. Consider constituting an EDI-AR committee |

EDI-AR and the Ultimate Program Goals of Residency Education

If we take a societal perspective and look at the desired outcomes of postgraduate medical education, it is to produce the next generation of superbly trained generalists and specialists who are prepared to care for the diverse populations they will serve in the future. Residency program commitment to EDI-AR is easily justified from this perspective. Serving populations well means strong attention to the inequities within society and requires a commitment to center both the margins and the structurally marginalized in how residency education is constructed.

There is another reason why we must address EDI-AR within our residency programs. The social contract between learner and teacher and learner and program is a fiduciary one. Programs and the teachers within them are bound to act in the best interests of the learners who join their programs and seek to be welcome within them. We must create the conditions whereby these learners can bring their whole selves to the work they do and to their learning, in a psychologically and culturally safe environment. Viewed through this relational ethics lens, there is moral imperative to promote diverse human flourishing within postgraduate medical education.

Conclusion

As you read further into this important Program Director companion, you will see the importance of the EDI-AR lens reflected in each of the topics, in each and every one of the chapters. This important work weaves seamlessly and logically through all that we do. We must have ongoing awareness of how this continues to be positively reflected in our work moving forward, with measurable outcomes that we are moving in the right direction for our learners, ourselves and most importantly our patients. We must continue to do better.

References

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/equity. Accessed 2022-05-06.

- Stote K. The coercive sterilization of aboriginal women in Canada. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 2012 Jan 1;36(3):117-50.

- Turbes S, Krebs E, Axtell S. The hidden curriculum in multicultural medical education: the role of case examples. Academic Medicine. 2002 Mar 1;77(3):209-16.

- Shore LM, Randel AE, Chung BG, Dean MA, Holcombe Ehrhart K, Singh G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of management. 2011 Jul;37(4):1262-89.

- Hafferty FW, Franks R. The hidden curriculum, ethics teaching, and the structure of medical education. Academic medicine. 1994 Nov.

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder A, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. American psychologist. 2007 May;62(4):271.